10.4 Deutsch’s algorithm

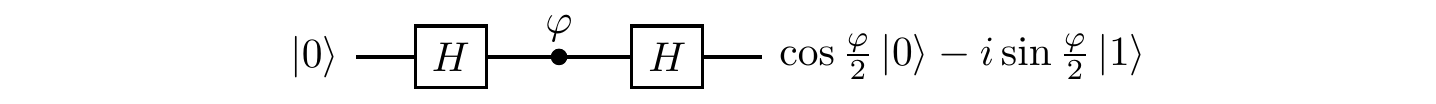

We start, once more, with the simplest quantum interference circuit

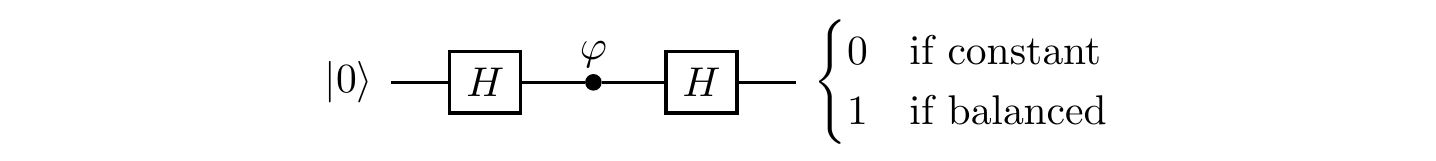

but let’s turn this into a black-box scenario, often known as the binary observable measurement problem:202

- we are allowed to prepare the input in any state that we like;

- we are allowed to read the output;

- but all we know about the value of

\varphi is that it is either0 or\pi , and we are not allowed to “look inside” the phase gate to see which value it is!

With these rules, can we figure out which value

Of course we can — we’re quantum information scientists!

One way of doing it is to prepare the input in the state

The very first quantum algorithm, proposed by David Deutsch in 1985, is very much related to this effect, but where the phase setting is determined by the Boolean function evaluation via the phase kick-back.

(Global properties of a one-bit function).

We are presented with an oracle that computes some unknown function

| constant | ||

| constant | ||

| balanced | ||

| balanced |

Our task is to determine, using the fewest queries possible, whether the function computed by the oracle is constant or balanced.

Note that we are not asked for the particular values

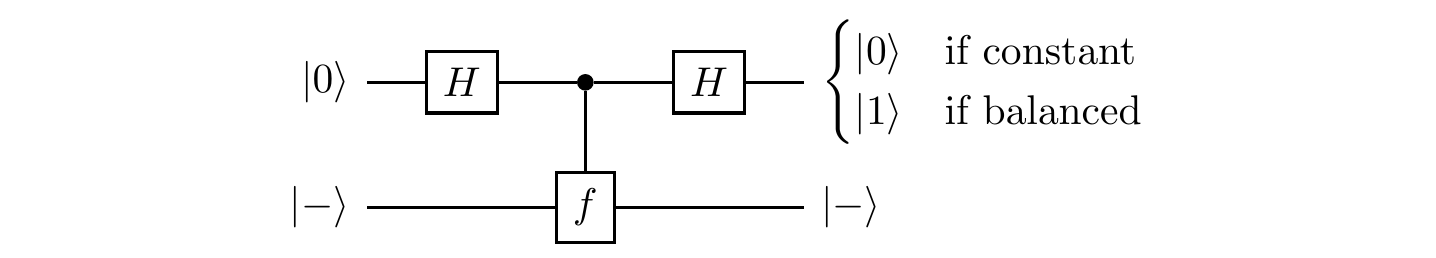

(Deutsch’s algorithm).

First register:

During the function evaluation, the second register “kicks back” the phase factor

The evolution of the first qubit is thus identical to that described by the circuit diagram

where the relative phase is

But really this is just the binary observable measurement problem in disguise!

Indeed, the fact that quantum Boolean function evaluation of a function

Deutsch’s result laid the foundation for the new field of quantum computation, and was followed by several other quantum algorithms for various problems. They all seem to rest on the same generic sequence:

- a Hadamard transform;

- function evaluation;

- another Hadamard (or Fourier) transform.205

As we shall see in a moment, in some cases (such as in Grover’s search algorithm) this sequence is repeated several times.

Let us now follow a tour through the three early quantum algorithms, where each one offers a higher-order speed-up when compared to their classical analogues than the last: firstly linear, then quadratic, and finally exponential. After this, we will look at generalising binary observable measurement, the corresponding algorithm analogous to Deutsch’s, and how this leads us to arguably the most famous quantum algorithm: Shor’s algorithm for prime factorisation.

You might recognise this as Exercise 2.14.8, and we will return to this problem again in Section 10.8.↩︎

The original version of Deutsch’s algorithm provides the correct answer with probability 50%. Here we present a modified/improved version. The more general problem, which deals with unknown functions

f\colon\{0,1\}^n\to\{0,1\} forn\geqslant 1 , is known as the Deutsch–Jozsa problem.↩︎This is also implemented in the Quantum Flytrap Virtual Lab.↩︎

As explained in Section 10.9, the Hadamard transform is a special case of the Fourier transform over the group

\mathbb{Z}_2^n .↩︎