3.1 Beam-splitters: physics against logic

A symmetric beam-splitter is a cube of glass which reflects half the light that impinges upon it, while allowing the remaining half to pass through unaffected.

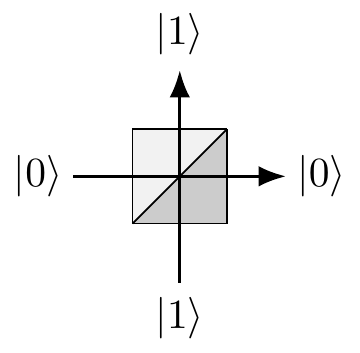

For our purposes it can simply be viewed as a device that has two input and two output ports, which we label with

Figure 3.1: A symmetric beam-splitter, with input ports on the bottom and the left sides, and output ports on the top and the right sides.

When we aim a single photon at such a beam-splitter using one of the input ports, we notice that the photon doesn’t split in two: we can place photo-detectors wherever we like in the apparatus, fire in a photon, and verify that if any of the photo-detectors registers a hit, none of the others do.

In particular, if we place a photo-detector behind the beam-splitter in each of the two possible exit beams, the photon is detected with equal probability at either detector, no matter whether the photon was initially fired into input port

If we fire the photon into the input port

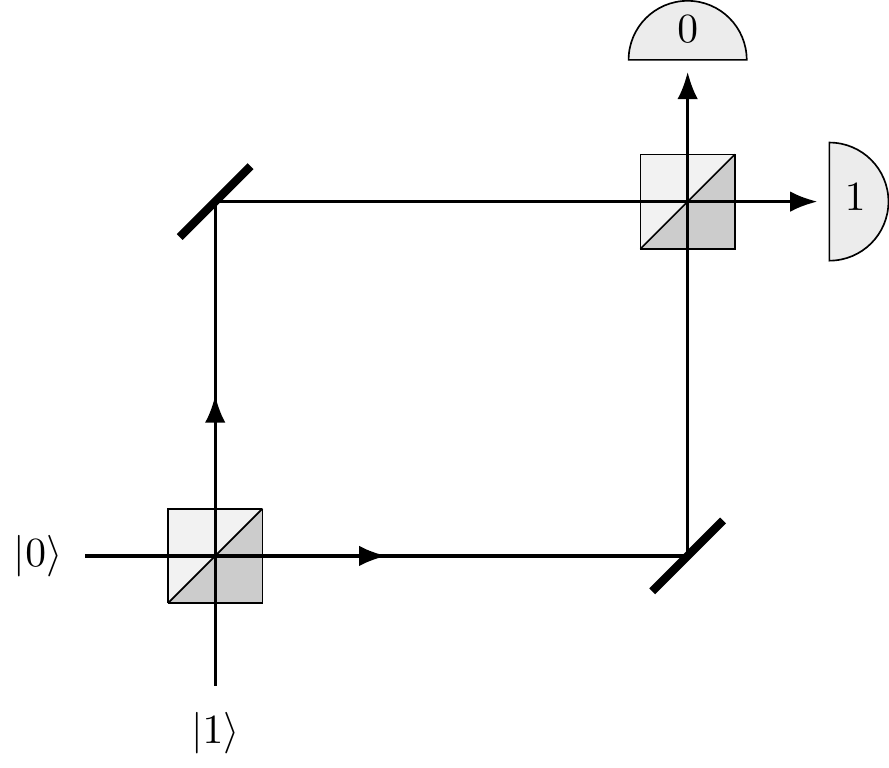

Figure 3.2: Two beam-splitters with mirrors, arranged so that the photon travels through both, along with two detectors. We label the detectors in such a way that, if a photon enters input

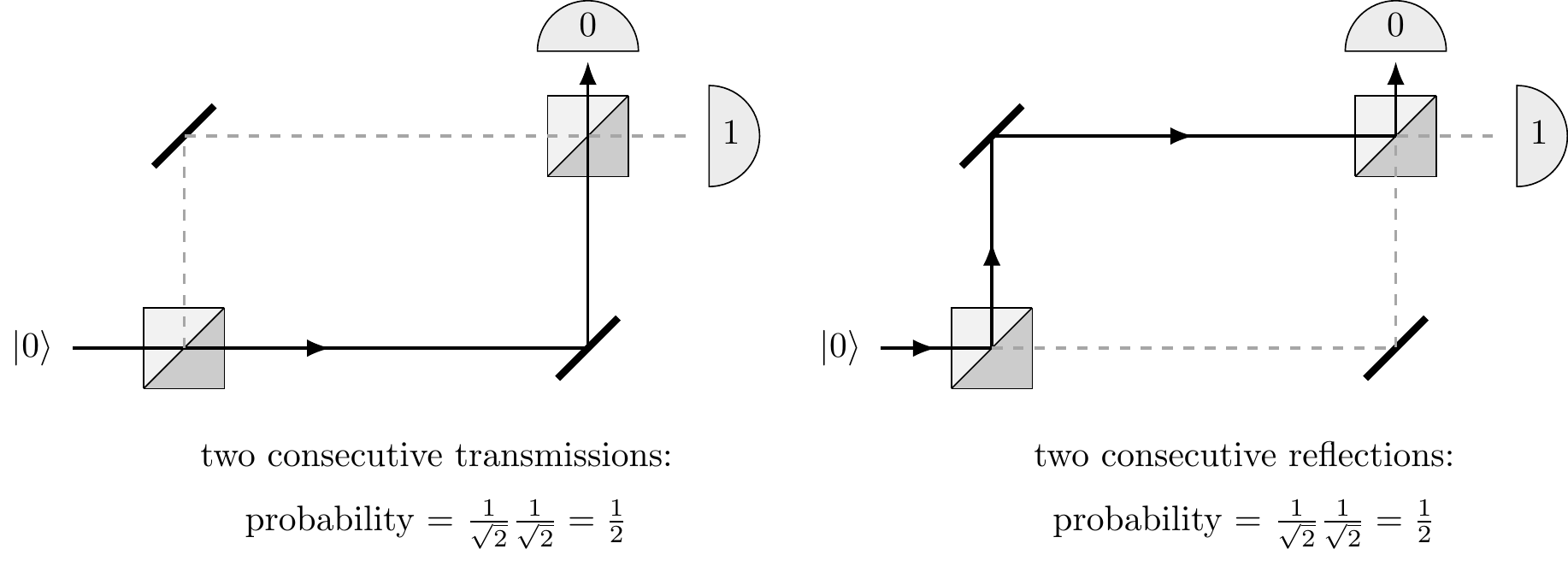

Recall the Kolmogorov additivity axiom in classical probability theory: whenever something can happen in several alternative ways, we add probabilities for each way considered separately.

We might argue that a photon fired into the input port

However, if we set up such an experiment in a lab, this is not what happens!

There is no reason why probability theory (or any other a priori mathematical construct for that matter) should make any meaningful statements about outcomes of physical experiments.

Figure 3.3: The two possible classical scenarios. Note that this is not what actually happens in the real physical world!

In experimental reality, when the optical paths between the two beam-splitters are the same, the photon fired from input port

The action of the beam-splitter — in fact, the action of any quantum device — can be described by tabulating the amplitudes of transitions between its input and output ports.66

Unlike probabilities, amplitudes can cancel each other out, witnessing destructive interference.

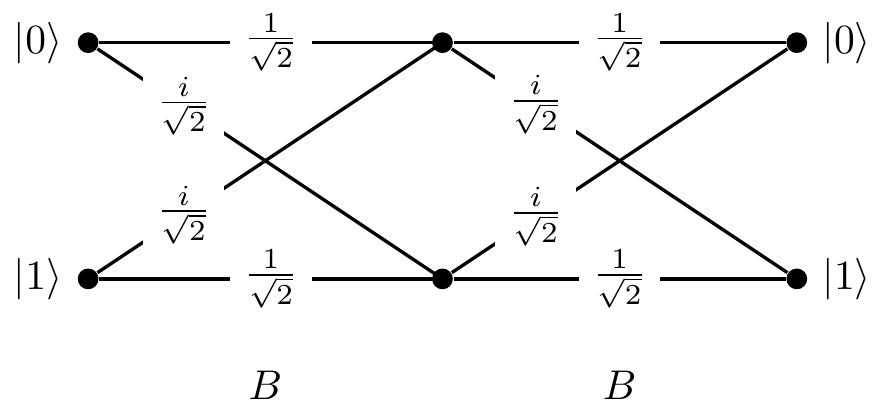

We can now go on and calculate the amplitude that the photon will reach detector

Figure 3.4: All possible transitions and their amplitudes when we compose two beam-splitters, as described by the matrix

However, instead of going through all the paths in this diagram and linking specific inputs to specific outputs, we can simply multiply the transition matrices:

| Bit-flip | ||

| Beam-splitter |

Note that gate

B is not the same square root of\texttt{NOT} as the one we have already seen. In fact, there are infinitely many ways of implementing this “impossible” logical operation.↩︎