5.6 Controlled-NOT

How do entangled states arise in real physical situations?

The short answer is that entanglement is the result of interactions.

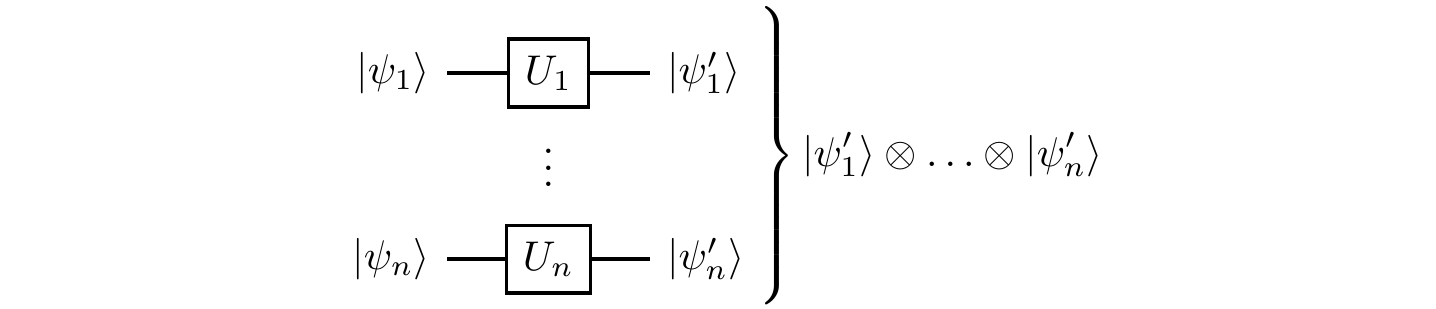

It is easy to see that tensor product operations

and so any collection of separable qubits remains separable. As soon as qubits start interacting with one another, however, they become entangled, and things start to get really interesting. We will describe interactions that cannot be written as tensor products of unitary operations on individual qubits.

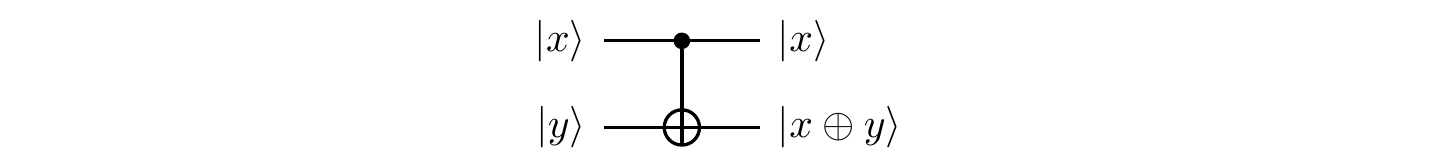

The most popular two-qubit entangling gate is the controlled-

| Controlled- |

We represent the

Figure 5.1: Where

Note that this gate does not admit any tensor-product decomposition, but can be written as a sum of tensor products:109

The

Here,

X\equiv\sigma_x refers to the Pauli operator that implements the bit-flip.↩︎Make sure that you understand how the Dirac notation is used here. More generally, think why

|0\rangle\langle 0|\otimes A + |1\rangle\langle 1|\otimes B means “if the first qubit is in state|0\rangle then applyA to the second one, and if the first qubit is in state|1\rangle then applyB to the second one”. What happens if the first qubit is in a superposition of|0\rangle and|1\rangle ?↩︎